Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

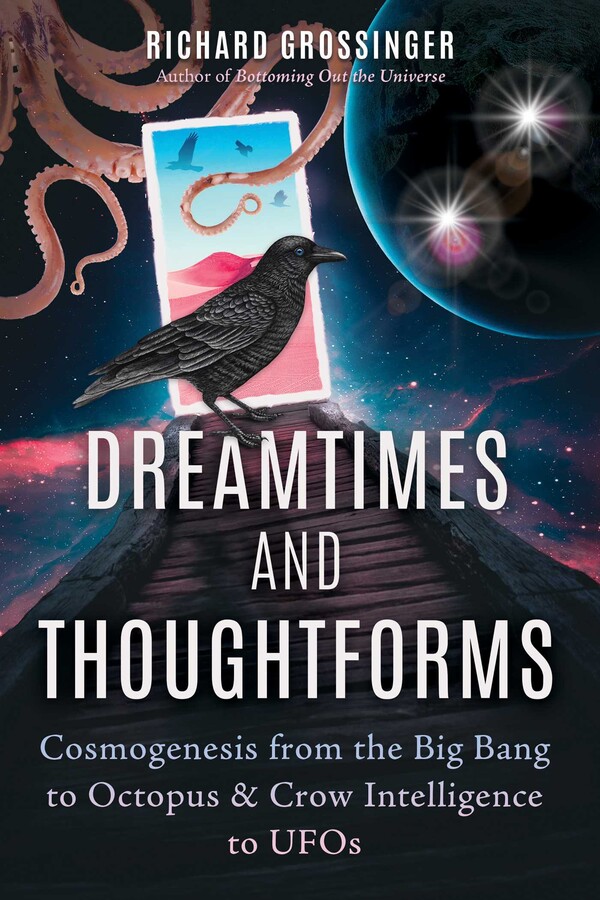

Dreamtimes and Thoughtforms

Cosmogenesis from the Big Bang to Octopus and Crow Intelligence to UFOs

Table of Contents

About The Book

• Looks at the Australian Aborigine Dreamtime as an attempt to understand the combined geological and geomantic landscape

• Investigates a range of ideas as they relate to the intersections of consciousness and reality, including reincarnation, past-life memories, ghosts, and UFOs

From the origins of the cosmos to the microbiome, COVID-19 pandemic, UFOs, and the shapeshifting of octopuses and language of crows, Richard Grossinger traverses the mysteries and enigmas that defi ne our universe and personal reality.

Beginning his narrative with the Big Bang, origin of the Milky Way, and birth of our solar system, Grossinger o ers a chronology of Earth’s geological, climatological, biological, and sociological evolution, leading to the current environmental and psychospiritual crisis. He explores the origin of cell life, RNA-DNA, and larger biomes, detailing in particular the remarkable intelligence of crows and octopuses. He uses the Australian Aborigine Dreamtime to understand landscapes as thoughtforms. He then o ers reimaginings, from the perspective of “dreamings,” of a wide variety of animals, including tardigrades, llamas, sea turtles, pigeons, bees, and coyotes.

Examining the scientifi c dilemmas and paradoxes of consciousness, time, and quantum entanglement, Grossinger carries these into the range of issues around reincarnation, past-life memories, messages from the afterlife, and ghosts. Sharing exercises from his personal practice, Grossinger makes a distinction between the Buddhist description of reality and how Buddhist practitioners create an operating manual for the universe and an assured path of salvation. The author then examines UFOs and their connections to elementals, fairies, and cryptids in terms of psychoids, Jung’s term for transconscious processes that enter our world as autonomous entities.

Taking the reader on a journey through the seen and unseen universe, from the Big Bang to the imaginal landscape of Dreamtime, Grossinger shows that matter is infused with spirit from its very beginning.

Excerpt

OCTOPUS AND CROW DREAMINGS

Creatures who share Gaia with us are souls too, living the same Dreamtime, wandering in its samsara, learning constraints and wonders of new bodies. Whales, elephants, owls, moles, skinks, and seals all have wisdoms, things to tell the universe, their gods, and us. We receive these gifts through their Dreamings and folkways. Otherwise, we are cooped, lonely beings in separate worlds.

While passing a pet shop advertising a new litter of hamsters in feltpen scrawl on window cardboard, I wondered, where do they all come from? The shop didn’t invent hamsters, though it might have bred them. For that matter, how do flies arise around a dead crab? Who are they?

If we all suddenly entered the astral field together, our hawk and salmon neighbors--even our mosquito and sow-bug neighbors--would look much like our human ones: autonomous souls. Remove karmically imposed costumes, and we are the same beings.

There is a reason that elephants attend funerals and memorial services, both elephant and human--they remember.

Octopuses and crows are, respectively, the most intelligent and talky invertebrates and birds. An octopus is a huge, highly evolved oyster with centers of intelligence and problem-solving coordinated in suckers along each of its eight arms, all reporting to a central ganglion. It is not an octo-pussie, it is an octo-hemispheric ganglion--a different branch of intelligence from anything else in the mammal class or vertebrate subphylum. It is more akin to a dweller in a Jovian sea, though Jupiter’s and Neptune’s “cephalopods” would have to be far more humongous to diffuse greater gravity, with bronchial cells evolved for methane metabolism.

In 2021, the United Kingdom recognized the invertebrate mind, adding an amendment to its Animal Welfare Sentience Bill, designating octopuses, crabs, squids, and lobsters along with “all other decapod crustaceans and cephalopod molluscs” as conscious beings.

Earth’s eight-tentacled, shell-less mollusks shapeshift in sensitive chaos and nonequilibrium flux, as they squeeze their whole bodies and arms into and through narrow rock and shell openings and researchers’ traps, finding the lone gap that matches their and the obstacle’s topology. They also figure out how to unscrew a jar containing a crab.

They rocket from hiding places with such sudden acceleration, sustained speed, stealth, and shape- and color-shifting that jump probabilities. This is what modern dancers and Continuum practitioners attempt with hominid bodies: genomic fluidity, embryogenic pluripotency.

Some observers have suggested that Cephalopods are not just overgrown Darwinian oysters but mutants of meteor-riding amino acids that splashed down from somewhere like the Sirius system or Pleiades and attached their strands to the genome of a Cambrian gastropod, conferring talents of elsewhere.

Other meteorite RNA could have hatched the fungal kingdom with its subterranean networks and entheogenic vistas by splicing alien codes into a proto-seaweed or haploid hornwort spore. Fiber-optic-like root languages may be native to many stellar systems.

Mushroom enthusiasts have proposed that mycology contains the E.T. talents and terms needed for solving our eco-crisis, delivered free from the stars: environmental clean-up (turning oil and gasoline waste into gardens of bee-gathering flowers); natural batteries (storing and releasing electrical charge); miracle medicines (cleaning cells and clearing malignancies); living machines (running factories, Teslas, and space stations); mortuary cycles (replacing crematory ash with topsoil); plus non-photosynthetic respiration, vegan cuisine, jazz and Bach-like madrigals (when electrodes are attached to their seeding bodies, unique melodies for different mushrooms)--and shamanic travels, interdimensional intelligence, attunement to Divine Love, voyeurism of Unity Consciousness, and acceptance of spirits and death.

Cephalopods inspire their own exobiological speculation. Though they didn’t fly here in saucer aquariums, their instructions might have ridden on comet cocoons:

“With a few notable exceptions, the octopus basically has a typical invertebrate genome that’s just been completely rearranged, like it’s been put in a blender and mixed,” said Caroline Albertin, marine biologist, at the University of Chicago. “This leads to genes being placed in new genomic environments with different regulatory elements and was an entirely unexpected find.”

Another interesting feature of this aquatic wonder is its ability to perfectly blend in with the surroundings. This chameleonic behavior is triggered by six protein genes named “reflectins” which impact the way light reflects off the octopus’ skin, thus turning it into assorted patterns and textures that camouflage the octopus. . .

These creatures evolved over a period of over 500 million years and are known to inhabit almost every body of water at nearly any depth. . . With all this “out of this world” evidence at hand, it’s hard not to see the otherworldly traits of octopuses, especially their ability to redesign their DNA for a flawless life experience and extreme survivability. Could this be just a complex and misunderstood evolutionary process? Or were these tentacled invertebrates brought to Earth from another place in the universe by some unknown civilization?13

The octopoid is more than a biomechanical projector of marine vistas; it conducts Husserlian phenomenology, Basquiat-like Neo-Expressionism, subaqueous neo-Platonism, and Yvonne Rainer choreography--all underwater with natural paints and textiles. Octopuses change their color-and-shape biomimicries, making themselves into effigies almost as realistic as anything brushed by Michelangelo or J. M. W. Turner. Their chromatophores paint in reds, blacks, and yellows; their deeper iridophores propriocept iridescent blues and greens. Deeper yet leucophores pearlesce as ambient whites while mirroring passing landscapes and objects. At the same time, the creature stretches sacs in its skin layers to replicate bands, stripes, and spots and uses papillae to form ridges and bumps. Cuttlefish propose Cephalopod ontology by effort-shape dynamics: dazzles of hue- and shapeshifting, hiding and reappearing in tactics of you-see-me-now, you-saw-me-then.

Works of molluscan body art generate credible rocks, kelp, other sea plants, black-and-white poisonous snakes, ocean bottom, even exotic paintings substituted for landscapes by scientists. The octopus faithfully turns into a rock or a fish or even a Miró. Mimicries are produced in instantaneous sequences, for its “critics” are onlooking predators, killer sharks and oversize groupers who render life-or-death verdicts.

Octopuses can make 150 to 200 such works of art in an hour!

In their diffuse eight-point intelligence, these chordates are more like collectives than any other sentient Gaian creatures. They speak to the myriad emanations of DNA wisdom. As the octopus rendition of the “Man from Galilee” goes, put your hand in the hand of the hand of the hand of the hand. . .

That is my way of saying that deeper sources of psi, precognition, telekinesis, and cell talk on this world go substantially unexplored.

Octopuses read the ocean and their own cell banks as they fluctuate and dart like underwater dervishes. Who knows what gods an octopus honors, what spirits she prays to, what tonglens she transmits through wounded seas.

Note, too, that, despite my invocation of a generic “octopus,” this is a wide-ranging clan, not a circus performer from Bozo under the Sea. There are as many octopuses as there are morphs and masks of mollusk protoplasm, with new ones still being discovered; for all we know, octopuses invent “octopuses” by the hour.

“Octopus” is otherwise a class: Cephalopoda. Its over 300 known species include nautilus, Atlantic pygmy, hammer, dumbo, southern blue-ringed, East Pacific red, as well as those hidden from our semiology in the deeper deep. Within a basic octo-limbed, decentralized oyster template, they encompass a variety of shapes, gowns, color displays, iridescences, sizes (capped by the great Antarctic squid), bioluminescences (the blue glowing coconut octopus among the most psychedelic).

Octopuses and a few squid and cuttlefish species, “routinely edit their RNA sequences to adapt to their environment. . .”

When such an edit happens, it can change how the proteins work, allowing the organism to fine-tune its genetic information without actually undergoing any genetic mutations. But most organisms don’t really bother with this method, as it’s messy and causes problems more often that solving them.

Researchers discovered that the common squid has edited more than 60 percent of RNA in its nervous system. Those edits essentially changed its brain physiology, presumably to adapt to various temperature conditions in the ocean.

DNA sequences were thought to exactly correspond with the sequence of amino acids in the resulting protein. However, it is now known that processes called RNA editing can change the nucleotide sequence of the mRNA molecules after they have been transcribed from the DNA. One such editing process, called A-to-I editing, alters the “A” nucleotide so that the translation machinery reads it as a “G” nucleotide instead. In some--but not all--cases, this event will change, or ‘recode’, the amino acid encoded by this stretch of mRNA, which may change how the protein behaves. This ability to create a range of proteins from a single DNA sequence could help organisms to evolve new traits.

[H]igh levels of RNA editing is not generally a molluscan thing; it’s an invention of the coleoid cephalopods.14

This natural CRISPR science makes it seem that cephalopods have mastered clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. But is it a native outgrowth or an interplanetary splice? Psi-like “cell talk” or a suppressed Chordate superpower? An axolotl-like specialty or a teachable rain dance? If biodynamic fields are fluid, shape-changing, and conduct epigenetic information, why eschew native resilience for commodity biotech?

The 2020 movie My Octopus Teacher has touched viewers in the way a flash drive from a trip to the Saturnian system, planet or moons, might: a visit with aliens whom we never knew (but with whom we share a solar system). Pippa Ehrlich and James Reed’s documentary transcends prior cartoons, tropes, and sushi. Diver Craig Foster befriends a female Octopus vulgaris in his local South African kelp forest. For the better part of a year, they swim together, do contact improv, and even kiss arms (octopus says hello, sucker by sucker, alien to hominid, E.T. to Elliott). They dance and play hide-and-seek with schools of fish. This makes sushi menus cannibalistic.

With its suckers, each tentacle-full bearing a rudimentary mind, mother octopus swiftly gathers a hundred or so shells around herself as shark protection and sits on ocean bottom like a lady’s fancy hat. As that hat, she rides the shark, the safest perch for a rodeo queen. She is a shell-covered changeling clown, as she masters her vertebrate predator. In a hypothetical Walt Disney version, hungry shark says, “W-w-w-here did that p-p-p-pesky oyster go.”

“Look on your back, bub!”

Foster remarks that his “friend” is more fundamentally intelligent than he is, for she is a giant underwater ganglion sprouting over hundreds of millions of years. When a shark bites off one of her arms, she convalesces for a while, deep in her small shell-and-kelp stone cave, foreshadowing Steven Spielberg’s E.T. There she grows a miniature arm that becomes a full-ledged tentacle. She jets about reborn.15

Octopuses have very short lives, proving that time, wisdom, and experience are nonlinear. Foster mourns the death of his young friend, who is old to herself, as she transfers her tidal lease and vital essence to her babes. She might well have flashed the words of Gautama Buddha: “I manifested in a dreamlike way to dreamlike beings and gave a dream-like dharma, but in reality I never taught and never actually came.”16

Crows are initiates by avian parameters, for they navigate mathematics of air and twig--no soft watery topologies for them. Conducting corvid algebra, geometrics, and geo-caching, they are grand empiricists and logicians, able to solve human-imposed puzzles involving different-sized pegs and a sequence of latches to get at food or drink. They can gauge, then beak-fill a beaker with tiny pebbles to raise its water level to their thirst.

As humanity’s shadow pets, these birds are well adapted to deforested suburbs and urban compost and decay. They understand a good cornfield, an overloaded truck, a litterbug picnic, a garbage transfer station, roadkill. Their talents include placing walnuts by car tires in traffic and retrieving the opened nuts at red lights.

A scarecrow in a field of corn is a relic of Neolithic magic, a stick sigil marking the boundary between human and bird.

Crows are not colorful like tanagers or toucans, but their tightly groomed feathers have an iridescent, satin sheen that contains the whole rainbow in the handsome way that old black-and-white films epitomize technicolor. They are among the most chromatic blacks I have seen. And their bodies are a perfect size, a compact avian doll. Neither eagle nor chickadee, they array, hop, pluck, and roost on rooftops and terraces with smug aplomb.

Crows and their close kin, ravens and magpies, don’t sing like songbirds but speak High Crow, a birdtalk with morphophonemics, dialects, and tonal and volume ranges for manifold occasions, including the clicks, glottal stops, and tonal flutterings (purrs) that characterize some African and Native American languages. Linguists have identified a vocabulary of 230 High Crow words and counting.

When you next hear big black birds cawing away on fences and rooftops or in the sylvan canopy or sky, don’t think that they are trying out their vocal cords, making a racket for the sake of it or repeating themselves from bird-brained OCD. Those are proto-sentences, syntactic formations with vibratory and tonal nuances beyond our ken. Those crows are holding full conversations, informing each other about situations in corvid culture, entrepreneurship, metabolism, and ontology, while gathering hominid ethnology and ethnography, as behavior of humans sets their agency. . . .

Product Details

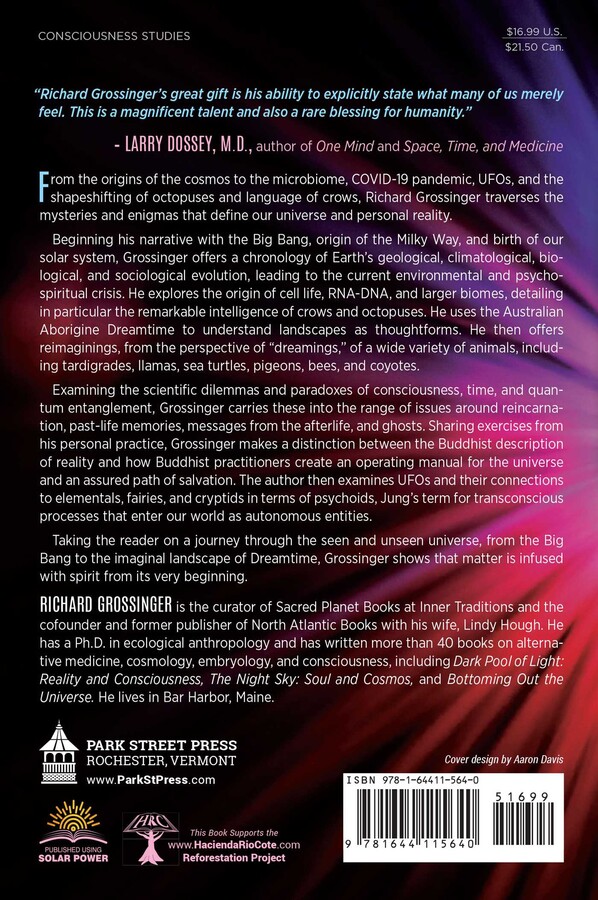

- Publisher: Park Street Press (December 14, 2022)

- Length: 192 pages

- ISBN13: 9781644115640

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Richard Grossinger’s great gift is his ability to explicitly state what many of us merely feel. This is a magnificent talent and also a rare blessing for humanity.”

– Larry Dossey, M.D., author of One Mind and Space, Time, and Medicine

“Grossinger hurls his mastery of esoteric wisdom, a profound understanding of the cosmos, and his exquisite poetic expression at the reader like the bright light of an asteroid whizzing past Earth’s orbit. A breathtaking read!”

– Patricia Cori, author, screenwriter, and former host of Beyond the Matrix

“We live in a wild cosmos, a multidimensional multiverse teeming with all sorts of intelligences and mysteries. Dreamtimes and Thoughtforms is an invitation into a bigger cosmological story that makes room for all the beauty and paradox we are enveloped in by (in)visible worlds. In these pages, Grossinger performs his trademark meta-integration magic--weaving together animal intelligence, UFOs, ghosts, and esoteric cosmologies into a wonderfully wild song of ourselves and the worlds around us, containing multitudes.”

– Sean Esbjörn-Hargens, Ph.D., dean of integral education at California Institute for Human Scien

“Dreamtimes and Thoughtforms examines the inner and external landscapes of consciousness. Exploring the primordial universe and/or multiverse, primitive biological life, physics, psi, dreams, philosophy, anthropology, and ancient writings, Grossinger goes beyond surface-level discussions and embraces deep contemplation and open-mindedness. Recognizing that consciousness is the builder of all we experience, the author realizes that one may survey the greater reality more effectively through inner vision than a set of eyes. When looking out to observe the external world, we, in some way, see a reflection of ourselves.”

– Mark Ireland, author of Soul Shift

“Dreamtimes and Thoughtforms takes forward, with new inputs, the project Alfred Jarry undertook in his Faustroll writings at the end of the nineteenth century. Like Jarry, Grossinger reads science through an esoteric lens and esoteric thinking through the lens of science, thus enriching our sensibilities, unmooring our imaginations. In his own terminology, perhaps Jarry was a preincarnation of Grossinger.”

– Fred D’Agostino, Ph.D., retired professor of humanities at the University of Queensland

“From the Big Bang to bacteria to the microbiomes, the Cambrian explosion, and catastrophic events, Richard Grossinger outlines the universe and the limitations of materialistic science in explaining ‘all that is,’ for there is more to life than math, chemistry, and physics. A great read; highly recommended.”

– John A. Rush, Ph.D., N.D., author of Jesus, Mushrooms, and the Origin of Christianity

“In Dreamtimes and Thoughtforms, the reader will learn about the spiritual concepts that date back to the Big Bang and how they relate to reincarnation, pastlife memories, ghosts, and even to the intelligence of crows and octopuses. This is a sensational investigation into how beliefs and thoughtforms create reality.”

– David Barreto, author of Spiritual Evolution in the Animal Kingdom

“Like his masterpiece Deep Pool of Light, the meanings flow from the pages to our souls, creating a new language of the sacred. Richard’s work is best seen perhaps as the scripture of an expanding cosmos written for a distant age beyond our present vision. It’s as though he can observe and celebrate from a distant galaxy our own Milky Way, nucleus to nova, or slide down a cosmic wormhole and document the journey!”

– Albert J. LaChance, author of Cultural Addiction and coauthor of The Third Covenant

“When I read Richard’s words I am uplifted and encouraged to fully envelop my mind in the psychospiritual, metaphysical spaces he makes so accessible. Dreamtimes and Thoughtforms is a profound treatise on the vanguard of how we cognize and ingest the super mundane and come to know the full expression of the living cosmos, all around and within.”

– Joshua Reichmann, filmmaker and musician

“Reminds me of a Bob Dylan song.”

– John Friedlander, author of Recentering Seth

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Dreamtimes and Thoughtforms Trade Paperback 9781644115640