Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

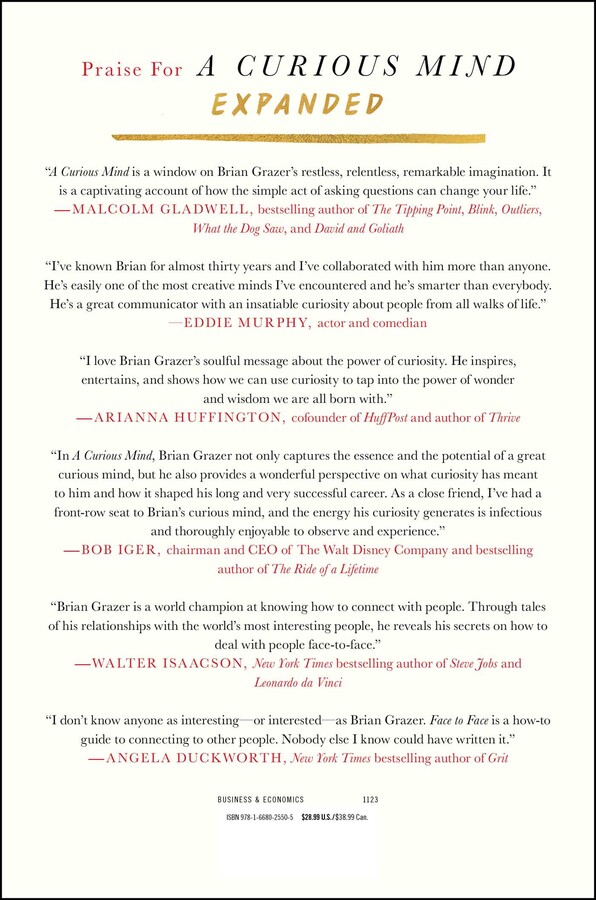

In this specially combined edition with a new foreword, Academy Award–winning producer Brian Grazer and acclaimed author Charles Fishman blend their insights from bestselling books A Curious Mind and Face to Face to transform the art of connecting with and through curiosity.

In A Curious Mind, deemed “a captivation account of how the simple act of asking questions can change your life” by Malcolm Gladwell, Grazer offers a brilliant peek into the “curiosity conversations” that inspired him to create some of the world’s most iconic movies and television shows. He shows how curiosity has been the “superpower” that fueled his rise as one of Hollywood’s leading producers and creative visionaries.

And in the captivating follow-up Face to Face, Grazer reveals that the secret to a more fulfilling life lies in personal connections, sparked through curiosity, learning through his interactions with people like Taraji P. Henson, Bill Gates, Barack Obama, Eminem, and Prince.

Now with a new foreword with fresh insights about curiosity from the last decade, A Curious Mind Expanded invites you to consider your personal journey of human connection. A fascinating page-turner, this combined edition offers a blueprint for how we can awaken our own curiosity and use it as a superpower in our own lives.

In A Curious Mind, deemed “a captivation account of how the simple act of asking questions can change your life” by Malcolm Gladwell, Grazer offers a brilliant peek into the “curiosity conversations” that inspired him to create some of the world’s most iconic movies and television shows. He shows how curiosity has been the “superpower” that fueled his rise as one of Hollywood’s leading producers and creative visionaries.

And in the captivating follow-up Face to Face, Grazer reveals that the secret to a more fulfilling life lies in personal connections, sparked through curiosity, learning through his interactions with people like Taraji P. Henson, Bill Gates, Barack Obama, Eminem, and Prince.

Now with a new foreword with fresh insights about curiosity from the last decade, A Curious Mind Expanded invites you to consider your personal journey of human connection. A fascinating page-turner, this combined edition offers a blueprint for how we can awaken our own curiosity and use it as a superpower in our own lives.

Excerpt

Introduction to the New Edition

Curiosity to the Rescue I think, at a child’s birth, if a mother could ask a fairy god- mother to endow that child with the most useful gift, that gift would be curiosity.—Eleanor Roosevelt 1

It was June 27, 2022, and I was at the United States Military Academy at West Point to deliver my son Patrick to his plebe year as a cadet.

That day was also the change-of-command ceremony for the head of West Point—the outgoing superintendent was being rede- ployed to be the head of U.S. Army forces across Europe and Africa—and I was in the audience to see the new head of West Point take command.

The ceremony was conducted by the Army Chief of Staff, Gen- eral James McConville, and all of a sudden, in the middle of this very formal, buttoned-down event, McConville said, “We have with us in the audience today an Oscar-winning movie producer—Brian Grazer.” And he pointed in my direction. I couldn’t have been more stunned. I smiled and nodded as people turned to look at me.

Then McConville said, “We’d really like him to make the Army version of Apollo 13.”

I get ideas for movies all the time, from all kinds of people.

But not usually delivered in public by the highest-ranking officer in the U.S. Army, in front of a hundred other senior officials of all kinds.

But McConville wasn’t really suggesting a movie idea. He was laying down a challenge.

After the ceremony, General McConville and another general found me in the audience, and he told me he was quite serious about trying to intrigue me with the possibility of getting the Army into the movies.

He certainly piqued my curiosity.

That’s how I came to find myself—just ten weeks later—strapped into an M1 Abrams tank, maneuvering in the middle of the desert.

That morning, I’d woken up at home in Santa Monica.

I’d gone with a handful of colleagues to an airport in Burbank, where we boarded a pair of Black Hawk helicopters and flew to Fort Irwin, the U.S. Army’s largest training center, which comprises about one thousand square miles of Mojave Desert, twice the land area of Los Angeles.

We’d watched soldiers training. We’d been shown a range of Army weapons and had the chance to fire some of them. We’d had a lunch of MREs, which are exactly as unappealing as you’ve heard. We’d tramped through the desert, ending up covered in dust.

And now, in the midafternoon, I was deep inside an M1, trying to absorb what it must be like to crew a battle tank for real—or even in one of Fort Irwin’s live-fire exercises. It was like nothing I’d ever done before—the confines of the tank cockpit, the heat (tanks don’t have air-conditioning), being immersed in the smell of metal and oil and lots of previous crew members.

During two days at Fort Irwin, we got up close with some of the equipment the Army uses every day—we hopped on and off those Black Hawks a half dozen times—and we also got to know scores of

young people, how they’d come to be in the U.S. Army, what they liked about it, what they didn’t like about it.

I wasn’t at Fort Irwin to learn how to drive an M1, of course. I was there, with a dozen people I make movies with, including a writer we’d asked to come along, to get a flavor of the U.S. military today, especially the people.

I was following my curiosity—we were all following our curiosity. What’s the modern Army like? What are the people in the Army like? Where’s the story moviegoers could connect with?

We learned a lot talking to the soldiers. Two things in particular have stuck with me.

I asked what was fun about being a soldier.

“Any time a group of us has a really hard task,” one soldier said, “and we’re sucking at it, that forms a bond. The tasks often aren’t fun, but the bonds we form doing them are. They’re rewarding.” More than rewarding, of course: That training creates the shared experi- ence and the trust that will serve these soldiers if they end up on a battlefield together.

Another soldier explained why, when we have such sophisticated drones, we still need people on the ground: soldiers trained, equipped, ready to deploy anywhere in the world.

Why ever put Americans directly in harm’s way?

Because, he said, it’s people who understand other people. “Human connection—human influence—that can’t happen with

drones,” the soldier said. “You win by influencing people, not killing them.”

And the way to influence people is with human connection. By showing up in person.

The soldiers we talked to were excited to give outsiders a taste of their world. And we were thrilled to spend two days out in the desert in Fort Irwin, away from screens and everything else, immersed in their world.

I’m compelled to take on the challenge of making an inspira- tional and highly entertaining action film about the men and women who sacrifice for our country as members of the United States Army. Given the fair share of Army films set on the battlefield, I want to ensure that this project is special and different than what we’ve al- ready seen.

And the points those two soldiers made will be woven through- out it: Sometimes life sucks, but if it sucks together, that creates con- nections and value that can’t be created any other way.

Curiosity allows us to reinvent the world, as we continue to innovate with new technologies like AI and expand our creativity. It’s impor- tant to note that curiosity cannot be found in anything other than humans. AI doesn’t have or initiate curiosity. It doesn’t have a con- sciousness; it doesn’t feel fear or pain; it can’t process feelings of hurt or a broken heart. But more distinctly, it doesn’t carry a soul. Artifi- cial intelligence is simply a patchwork of those human ingredients to create seemingly original and authentic stories. It’s our responsibility to remember the difference.

Curiosity is the tool we use to solve problems—big problems, urgent problems, and our own problems. It was the curiosity of people who run pasta companies and flour mills, mask factories and seaports and middle schools. And every one of our own families too. With AI in the mix, both human curiosity and contact will become all the more powerful in the era of tech.

Having lived through uncertainty reminds us of the uncertainty we live with every day. If you don’t understand a problem, you can’t fix it. And the first step to understanding is leaning into the uncer- tainty, leaning into the not knowing. Asking questions. Curiosity opens the door to adaptability. Curiosity also opens the door to empathy.

In the last decade, I wrote two books that tried to capture the two most important things I’d learned to that point in my life:

A Curious Mind is about the underrated power of curiosity to help you live a better life.

Face to Face is about the power of human contact face to face— the importance of being with people in person. Because being in the room changes everything.

Those two deceptively simple concepts are really a single whole idea—they are the yin and yang of human connection, and also of discovery.

Nothing has so reinforced those two ideas—for me, but also in our wider cultures—as the pandemic years have: Curiosity, because of its absolute indispensability to how the world survived COVID-19. And human connection, because of how its absence during the pan- demic shriveled our sense of well-being, underscoring so vividly how central our human connections are not just to surviving emotionally but to thriving.

To live a life with both meaning and happiness, we need curiosity, and we need each other—and those two things in turn reinforce each other.

And so as we reinvent ourselves, we’re putting out a fresh edition combining the two books into a single volume: A Curious Mind Expanded.

Curiosity isn’t just a tool for figuring out the structure of a mole- cule or how to tell a story about the Army.

It is that, of course. A tool to learn about how the world works. But curiosity is also a way of bridging gaps. Curiosity is itself a tool of human connection. If you ask someone a sincere question and lis- ten to the answer with an open mind (and an open heart), you’re learning how that person sees the world.

Curiosity is a tool of empathy. It is as powerful for helping us re-

late to each other as it is at helping us design faster computer chips. Through the politics of the last decade, through the social divi- sions and uncertainty, we needed fewer snap judgments and fewer

assumptions and more genuine curiosity.

One of the things that’s magic about curiosity is that you don’t need anyone’s permission to use it, you don’t need a team, and you don’t need any special tools you don’t have with you all the time.

Curiosity is a mind-set.

It’s the mind-set that sees something—in the newspaper, or on TikTok or Instagram—and doesn’t say, “What an idiot!” but “Why would she think that? Hmm.”

Another powerful quality of curiosity is that it’s positively rein- forcing. If you approach the world with questions, you get one of three experiences:

You learn something completely new.

Or you learn that something you thought you understood is dif- ferent than you thought.

Or you learn that you were right.

One of those three things always happens.

That’s why I love asking questions. I really love all three of those results. Whether I was ignorant or confused or right, I’m never sorry I asked the questions.

This is true, and obvious, when it comes to our intellectual pur- suits. But it’s just as true—it’s just as powerful—in our relationships with other people.

Here’s a very personal example.

My son Patrick was finishing high school, and he still had to pick and apply to colleges. One of his friends had gotten into West Point, and Patrick was impressed with the experience his friend had there. From never having shown any particular interest in the military, or in going to West Point, Patrick moved over the course of a year to de- ciding that West Point was his first choice for college. Not many parents I know have kids who go to the military acad- emies. I was baffled. I was puzzled. And yes, I was worried: Everyone who graduates from West Point spends eight years as a commis- sioned officer in the U.S. Army, and I don’t know any parents who want their kids to go to war. Not to mention that West Point is a stunningly demanding place to go to school—it’s not the stereotypi- cal college experience.

I remember a particular conversation I had with Patrick that opened my eyes. He told me two things that will always stay with me.

First, he said, “The things I care about are embodied in the values of West Point. Service to country. Service to one another.”

He wanted to go to a college that would teach him, explicitly, to put those values into practice every day.

And then Patrick said, “Dad, you like to be challenged. I know that. I’ve seen it growing up. But I like to be challenged too. I like to be challenged even more than you do. I like to be challenged every minute of every day.”

You probably couldn’t find a better one-sentence description of West Point than that: Challenged every minute of every day.

I know my son well, and I love him—and all my children—with all my heart. This was a conversation that changed how I saw Pat- rick. I wasn’t so much surprised as I was impressed and humbled.

I’d asked the simplest of questions about this key decision he was making—a decision, frankly, I disagreed with. The result was that I discovered my son had grown up. He’d thought about this carefully, thoughtfully. He was much less naive about it than I was, in fact. He understood himself, he understood his convictions, he understood what he was looking for, and he understood what he was getting himself into.

And that’s how I became the father of a West Point cadet.

We often get confused about something that has to do with curiosity—confused or maybe even a little scared. It seems easier, or safer, to fall back on our easy assumptions, es-

pecially if those assumptions reinforce what we already think.

We think that if we ask a sincere and thoughtful question of someone we disagree with, we might be dragged into an argument or coerced into agreeing with their opposing viewpoint.

Neither is correct.

It’s often just the opposite. When you use curiosity with thought- fulness and compassion, you don’t have to agree with that person. But, you end up understanding them better, and that understanding is a form of connection.

So you’re holding a book that does two things:

It asks you to ask more questions—to recognize the power of your own curiosity, to help you at work, to help you at home, to help you make friends, hold people accountable, discover what you love. Curiosity doesn’t require a crisis. It doesn’t even require an occasion. It can add depth and empathy, insight and joy and understanding to your life, moment by moment.

And this book asks you—whenever possible—to see people in person. To meet them, to look them in the eye. And it tells what I hope are memorable stories about how that changes your conversa- tions and your relationships—and why.

In early 2023, we got the latest results from an extraordinary study on human satisfaction and human health—the longest, most detailed longitudinal study of people in history. It’s the Harvard Study of Adult Development, begun in 1938, which has tracked hundreds of people, and their spouses and children, through eight decades.

The core finding of the study, which is now irrefutable, has sur- prised even the scientists conducting the research: human connec- tion, our relationships, are the most important thing to our happiness, our satisfaction with our lives, and our actual physical health. Strong relationships with family and friends are a better pre-

dictor of happiness, and also of health and longevity, than income or IQ, than genetics or your cholesterol. That’s a stunning and priceless insight.

Curiosity and connection. The keys to a long and happy life, and a satisfying and interesting one as well.

Brian Grazer May 2023

Curiosity to the Rescue I think, at a child’s birth, if a mother could ask a fairy god- mother to endow that child with the most useful gift, that gift would be curiosity.—Eleanor Roosevelt 1

It was June 27, 2022, and I was at the United States Military Academy at West Point to deliver my son Patrick to his plebe year as a cadet.

That day was also the change-of-command ceremony for the head of West Point—the outgoing superintendent was being rede- ployed to be the head of U.S. Army forces across Europe and Africa—and I was in the audience to see the new head of West Point take command.

The ceremony was conducted by the Army Chief of Staff, Gen- eral James McConville, and all of a sudden, in the middle of this very formal, buttoned-down event, McConville said, “We have with us in the audience today an Oscar-winning movie producer—Brian Grazer.” And he pointed in my direction. I couldn’t have been more stunned. I smiled and nodded as people turned to look at me.

Then McConville said, “We’d really like him to make the Army version of Apollo 13.”

I get ideas for movies all the time, from all kinds of people.

But not usually delivered in public by the highest-ranking officer in the U.S. Army, in front of a hundred other senior officials of all kinds.

But McConville wasn’t really suggesting a movie idea. He was laying down a challenge.

After the ceremony, General McConville and another general found me in the audience, and he told me he was quite serious about trying to intrigue me with the possibility of getting the Army into the movies.

He certainly piqued my curiosity.

That’s how I came to find myself—just ten weeks later—strapped into an M1 Abrams tank, maneuvering in the middle of the desert.

That morning, I’d woken up at home in Santa Monica.

I’d gone with a handful of colleagues to an airport in Burbank, where we boarded a pair of Black Hawk helicopters and flew to Fort Irwin, the U.S. Army’s largest training center, which comprises about one thousand square miles of Mojave Desert, twice the land area of Los Angeles.

We’d watched soldiers training. We’d been shown a range of Army weapons and had the chance to fire some of them. We’d had a lunch of MREs, which are exactly as unappealing as you’ve heard. We’d tramped through the desert, ending up covered in dust.

And now, in the midafternoon, I was deep inside an M1, trying to absorb what it must be like to crew a battle tank for real—or even in one of Fort Irwin’s live-fire exercises. It was like nothing I’d ever done before—the confines of the tank cockpit, the heat (tanks don’t have air-conditioning), being immersed in the smell of metal and oil and lots of previous crew members.

During two days at Fort Irwin, we got up close with some of the equipment the Army uses every day—we hopped on and off those Black Hawks a half dozen times—and we also got to know scores of

young people, how they’d come to be in the U.S. Army, what they liked about it, what they didn’t like about it.

I wasn’t at Fort Irwin to learn how to drive an M1, of course. I was there, with a dozen people I make movies with, including a writer we’d asked to come along, to get a flavor of the U.S. military today, especially the people.

I was following my curiosity—we were all following our curiosity. What’s the modern Army like? What are the people in the Army like? Where’s the story moviegoers could connect with?

We learned a lot talking to the soldiers. Two things in particular have stuck with me.

I asked what was fun about being a soldier.

“Any time a group of us has a really hard task,” one soldier said, “and we’re sucking at it, that forms a bond. The tasks often aren’t fun, but the bonds we form doing them are. They’re rewarding.” More than rewarding, of course: That training creates the shared experi- ence and the trust that will serve these soldiers if they end up on a battlefield together.

Another soldier explained why, when we have such sophisticated drones, we still need people on the ground: soldiers trained, equipped, ready to deploy anywhere in the world.

Why ever put Americans directly in harm’s way?

Because, he said, it’s people who understand other people. “Human connection—human influence—that can’t happen with

drones,” the soldier said. “You win by influencing people, not killing them.”

And the way to influence people is with human connection. By showing up in person.

The soldiers we talked to were excited to give outsiders a taste of their world. And we were thrilled to spend two days out in the desert in Fort Irwin, away from screens and everything else, immersed in their world.

I’m compelled to take on the challenge of making an inspira- tional and highly entertaining action film about the men and women who sacrifice for our country as members of the United States Army. Given the fair share of Army films set on the battlefield, I want to ensure that this project is special and different than what we’ve al- ready seen.

And the points those two soldiers made will be woven through- out it: Sometimes life sucks, but if it sucks together, that creates con- nections and value that can’t be created any other way.

Curiosity allows us to reinvent the world, as we continue to innovate with new technologies like AI and expand our creativity. It’s impor- tant to note that curiosity cannot be found in anything other than humans. AI doesn’t have or initiate curiosity. It doesn’t have a con- sciousness; it doesn’t feel fear or pain; it can’t process feelings of hurt or a broken heart. But more distinctly, it doesn’t carry a soul. Artifi- cial intelligence is simply a patchwork of those human ingredients to create seemingly original and authentic stories. It’s our responsibility to remember the difference.

Curiosity is the tool we use to solve problems—big problems, urgent problems, and our own problems. It was the curiosity of people who run pasta companies and flour mills, mask factories and seaports and middle schools. And every one of our own families too. With AI in the mix, both human curiosity and contact will become all the more powerful in the era of tech.

Having lived through uncertainty reminds us of the uncertainty we live with every day. If you don’t understand a problem, you can’t fix it. And the first step to understanding is leaning into the uncer- tainty, leaning into the not knowing. Asking questions. Curiosity opens the door to adaptability. Curiosity also opens the door to empathy.

In the last decade, I wrote two books that tried to capture the two most important things I’d learned to that point in my life:

A Curious Mind is about the underrated power of curiosity to help you live a better life.

Face to Face is about the power of human contact face to face— the importance of being with people in person. Because being in the room changes everything.

Those two deceptively simple concepts are really a single whole idea—they are the yin and yang of human connection, and also of discovery.

Nothing has so reinforced those two ideas—for me, but also in our wider cultures—as the pandemic years have: Curiosity, because of its absolute indispensability to how the world survived COVID-19. And human connection, because of how its absence during the pan- demic shriveled our sense of well-being, underscoring so vividly how central our human connections are not just to surviving emotionally but to thriving.

To live a life with both meaning and happiness, we need curiosity, and we need each other—and those two things in turn reinforce each other.

And so as we reinvent ourselves, we’re putting out a fresh edition combining the two books into a single volume: A Curious Mind Expanded.

Curiosity isn’t just a tool for figuring out the structure of a mole- cule or how to tell a story about the Army.

It is that, of course. A tool to learn about how the world works. But curiosity is also a way of bridging gaps. Curiosity is itself a tool of human connection. If you ask someone a sincere question and lis- ten to the answer with an open mind (and an open heart), you’re learning how that person sees the world.

Curiosity is a tool of empathy. It is as powerful for helping us re-

late to each other as it is at helping us design faster computer chips. Through the politics of the last decade, through the social divi- sions and uncertainty, we needed fewer snap judgments and fewer

assumptions and more genuine curiosity.

One of the things that’s magic about curiosity is that you don’t need anyone’s permission to use it, you don’t need a team, and you don’t need any special tools you don’t have with you all the time.

Curiosity is a mind-set.

It’s the mind-set that sees something—in the newspaper, or on TikTok or Instagram—and doesn’t say, “What an idiot!” but “Why would she think that? Hmm.”

Another powerful quality of curiosity is that it’s positively rein- forcing. If you approach the world with questions, you get one of three experiences:

You learn something completely new.

Or you learn that something you thought you understood is dif- ferent than you thought.

Or you learn that you were right.

One of those three things always happens.

That’s why I love asking questions. I really love all three of those results. Whether I was ignorant or confused or right, I’m never sorry I asked the questions.

This is true, and obvious, when it comes to our intellectual pur- suits. But it’s just as true—it’s just as powerful—in our relationships with other people.

Here’s a very personal example.

My son Patrick was finishing high school, and he still had to pick and apply to colleges. One of his friends had gotten into West Point, and Patrick was impressed with the experience his friend had there. From never having shown any particular interest in the military, or in going to West Point, Patrick moved over the course of a year to de- ciding that West Point was his first choice for college. Not many parents I know have kids who go to the military acad- emies. I was baffled. I was puzzled. And yes, I was worried: Everyone who graduates from West Point spends eight years as a commis- sioned officer in the U.S. Army, and I don’t know any parents who want their kids to go to war. Not to mention that West Point is a stunningly demanding place to go to school—it’s not the stereotypi- cal college experience.

I remember a particular conversation I had with Patrick that opened my eyes. He told me two things that will always stay with me.

First, he said, “The things I care about are embodied in the values of West Point. Service to country. Service to one another.”

He wanted to go to a college that would teach him, explicitly, to put those values into practice every day.

And then Patrick said, “Dad, you like to be challenged. I know that. I’ve seen it growing up. But I like to be challenged too. I like to be challenged even more than you do. I like to be challenged every minute of every day.”

You probably couldn’t find a better one-sentence description of West Point than that: Challenged every minute of every day.

I know my son well, and I love him—and all my children—with all my heart. This was a conversation that changed how I saw Pat- rick. I wasn’t so much surprised as I was impressed and humbled.

I’d asked the simplest of questions about this key decision he was making—a decision, frankly, I disagreed with. The result was that I discovered my son had grown up. He’d thought about this carefully, thoughtfully. He was much less naive about it than I was, in fact. He understood himself, he understood his convictions, he understood what he was looking for, and he understood what he was getting himself into.

And that’s how I became the father of a West Point cadet.

We often get confused about something that has to do with curiosity—confused or maybe even a little scared. It seems easier, or safer, to fall back on our easy assumptions, es-

pecially if those assumptions reinforce what we already think.

We think that if we ask a sincere and thoughtful question of someone we disagree with, we might be dragged into an argument or coerced into agreeing with their opposing viewpoint.

Neither is correct.

It’s often just the opposite. When you use curiosity with thought- fulness and compassion, you don’t have to agree with that person. But, you end up understanding them better, and that understanding is a form of connection.

So you’re holding a book that does two things:

It asks you to ask more questions—to recognize the power of your own curiosity, to help you at work, to help you at home, to help you make friends, hold people accountable, discover what you love. Curiosity doesn’t require a crisis. It doesn’t even require an occasion. It can add depth and empathy, insight and joy and understanding to your life, moment by moment.

And this book asks you—whenever possible—to see people in person. To meet them, to look them in the eye. And it tells what I hope are memorable stories about how that changes your conversa- tions and your relationships—and why.

In early 2023, we got the latest results from an extraordinary study on human satisfaction and human health—the longest, most detailed longitudinal study of people in history. It’s the Harvard Study of Adult Development, begun in 1938, which has tracked hundreds of people, and their spouses and children, through eight decades.

The core finding of the study, which is now irrefutable, has sur- prised even the scientists conducting the research: human connec- tion, our relationships, are the most important thing to our happiness, our satisfaction with our lives, and our actual physical health. Strong relationships with family and friends are a better pre-

dictor of happiness, and also of health and longevity, than income or IQ, than genetics or your cholesterol. That’s a stunning and priceless insight.

Curiosity and connection. The keys to a long and happy life, and a satisfying and interesting one as well.

Brian Grazer May 2023

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (April 17, 2024)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781668025505

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): A Curious Mind Expanded Edition Hardcover 9781668025505

- Author Photo (jpg): Brian Grazer Sage Grazer(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit

- Author Photo (jpg): Charles Fishman Photograph © Lidia Gjorjievska(1.3 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit