Plus get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

“After five decades, twenty books, and countless columns, [John Gierach] is still a master” (Forbes). Now, in his latest fresh and original collection, Gierach shows us why fly-fishing is the perfect antidote to everything that is wrong with the world.

“Gierach’s deceptively laconic prose masks an accomplished storyteller...His alert and slightly off-kilter observations place him in the general neighborhood of Mark Twain and James Thurber” (Publishers Weekly). In Dumb Luck and the Kindness of Strangers, Gierach looks back to the long-ago day when he bought his first resident fishing license in Colorado, where the fishing season never ends, and just knew he was in the right place. And he succinctly sums up part of the appeal of his sport when he writes that it is “an acquired taste that reintroduces the chaos of uncertainty back into our well-regulated lives.”

Lifelong fisherman though he is, Gierach can write with self-deprecating humor about his own fishing misadventures, confessing that despite all his experience, he is still capable of blowing a strike by a fish “in the usual amateur way.” The “voice of the common angler” (The Wall Street Journal), he offers witty, trenchant observations not just about fly-fishing itself but also about how one’s love of fly-fishing shapes the world that we choose to make for ourselves.

Excerpt

1. CLOSE TO HOME

I live in the foothills of the northern Colorado Rockies with dozens of trout streams within day-trip range, so it’s easy for me to recommend fishing close to home. The advantages are obvious. You can play hooky to go fishing at a moment’s notice; it only takes one trip to the pickup to pack your minimal gear (you know how little you need because you need so little); you know right where you want to go and have plenty of backups in case someone has high-graded your spot; and a rained-out day isn’t a deal breaker—you just go home and come back when the creek clears. Eventually fishing becomes such a normal part of daily life that you can stop for a half gallon of milk on the way home.

I understand that not everyone is so lucky; a precious few have it easier, but most have it harder. I might once have said that you make that kind of luck for yourself, and in some ways you do, but it’s just as often true that people end up where they are through no fault of their own and are then faced with making the best of it.

I know that because I’ve temporarily ended up in a few places I didn’t care for over the years (Cleveland comes immediately to mind), but I was young and unattached enough to be able to move on as soon as I comprehended my predicament. I may also have understood that the option to move on would begin to wane with the accumulation of possessions and entanglements, which at the time only made the idea of blowing town seem more attractive. In fact, there were a number of years when literally or figuratively blowing town at the slightest provocation was my modus operandi.

I didn’t exactly weigh all my options before I finally bought property and sank roots where I am now; it was just that when the opportunity came for that to happen I liked where I was and thought, Why not? I’d recently turned thirty and my father had died, leaving me a small inheritance: two things I didn’t see coming. A few years earlier this might have gone differently, but by then I was just old enough to realize I only had two choices here: wake up in five years dead broke and with an epic hangover, or spend the whole wad on something I could hold on to and make use of, like a house. There were those in my family who said my modest windfall would be enough for a down payment on a nice little starter home in a decent neighborhood, but they’d overlooked my position as someone with no credit rating who’d be hard-pressed to convince a bank that I was “employed” as a freelance writer. Even I could see I wasn’t the type to come up with a mortgage payment once a month like clockwork.

So I found a wretched but habitable little house with an asking price of about what I had on hand and bought it outright. It was the cheapest house for sale in the county and with good reason, but it was within walking distance of a sleepy little town I liked and across the road from a trout stream I fished often, which made up for a lot. There was a tense moment when the seller balked—even though people weren’t exactly lining up to buy this place—but in a rare burst of insight I realized he’d taken one look at me and assumed a cash transaction of this size must involve drug money. So I took him aside and straightened him out. He said he was sorry to hear about my dad and the deal went through.

As I said, I already knew and liked the stream across the road from my new house, but with a home base just downstream of the confluence of its three forks, I set out to explore the entire drainage as time permitted. The majority of it was on federal land—national forest, national park, and wilderness area—that was sometimes difficult to reach, but at least it was public. A few stretches lower down were private and had to be finessed in one way or another. (By that I mean I always at least tried to get permission.) The project went on for decades in a haphazard way and I can’t swear that it was ever actually completed, but to this day if someone asks me what’s down in here or way up there I can tell them in convincing detail.

Naturally I discovered some sweet spots that held good-size trout and where I never saw another soul and I believed—or wanted to believe—that these places were unknown to anyone except one young, intrepid trout bum. That was the kind of glamorous notion that’s irresistible at a certain age, even though it stretches the bounds of belief.

Some years later, on a junket to Canada’s Northwest Territories, a friend and I talked a guide into taking us to some bona fide virgin water. It was a feeder creek that the lodge we were fishing from—the only lodge that had ever operated in the region—knew for sure they’d never taken sports to. Furthermore, this wasn’t the kind of place First Nation netters would ever have gone; they’d have stuck with the bigger water that would be easier to fish and yield better hauls.

So we alternately paddled and walked a canoe a few miles up that creek, where we caught arctic grayling weighing around a pound each and some hammer-handle-size pike. The only thing that was exceptional about the place was that we were pretty sure we were the first ones to ever fish there. It was an ambition satisfied, but by then new ideas about preservation had stolen the romance from the notion of breaking new sod like a pioneer and replaced it with the sneaking suspicion that maybe we humans, with our monstrous egos and appetites, should leave a few places unspoiled. So I came away with mosquito bites and mixed feelings. I never felt guilty about fishing there, but I wasn’t as pleased with myself as I’d expected to be and I dropped the part of the fantasy where I named the creek and then went on to live long enough to see that name on a map.

As time went on I worked hard, or at least steadily, traveled more, and finally reached a point where I actually could convince a bank I was gainfully employed as a writer. But I’d never developed the habit of borrowing, so the only time I actually did it I got so creeped out that I paid off the loan early, incidentally saving myself a pile in interest. As Craig Nova said, “Credit is a good friend, but a hard master, while cash is a constant like the speed of light.”

Another constant was the water near home that I’d become thoughtlessly familiar with and felt I knew better than anyone. My evidence was—and still is—that when the streams are fishable I know where to go, what fly to tie on, and where and how to cast in order to catch trout. (More and bigger trout than any other competent fly-fisher could manage? I like to think so, but who’s to say?) Sometimes I’m even able to pick the species I feel like catching: brown trout lower down, shading to brook trout at higher elevations, and finally to some cutthroats holding on way up in the high country, where the streams are cold and narrow and the season is short. The transitions between species are indistinct; they occur at different elevations depending on the creek, and they’ll sometimes move around from year to year, but seldom by more than a mile or so. Of course that’s not counting fish that pop up unexpectedly where I’ve come to think they shouldn’t be, but then however intimately you think you know a stream it can still surprise you.

A good-size trout in any of these creeks will be around 10 inches long, with plenty smaller and a few larger. A 12- or 14-incher is a real nice fish and in the forty-plus years I’ve fished here I’ve landed a handful in the neighborhood of 16 inches, including one lovely cutthroat that almost brought me to tears and probably would have if there hadn’t been a witness present. And more recently there was an 18-inch brown that made me glad I had a witness along to measure the fish and back up my story. But even then we got looks from friends that suggested they thought we’d shared a recently legalized doobie and gotten hysterical about a 14-incher. I was insulted at first, but then decided that if anyone chose not to believe in the hidden pool where the big trout lives, it was okay with me.

I’ve caught larger and more exotic fish elsewhere. I wouldn’t trade a minute of that, and plan to do it again as often as possible, but this modest, hometown water where the benchmark trout will always be around nine or 10 inches long is a fine thing to come home to, regardless of where I’ve been. This isn’t the kind of destination water that attracts hordes of technicians and headhunters. It’s fished mostly by locals and the odd tourist with a day to kill. For decades its well-deserved reputation for mediocrity has saved it, although that’s not to say it hasn’t changed.

In the years I’ve fished here there have been high runoffs, and one massive thousand-year flood that profoundly rearranged the drainage in places, not to mention droughts—some lasting as long as five seasons—plus all the other natural and man-made slings and arrows trout streams are heir to. In some big snowpack years the water stayed so high and cold that there was virtually no fishing season at all unless you wanted to resort to worms and sinkers. But fish eat well in high water, so the following year, after a more or less normal runoff receded, the trout were big and fat and there were lots of them. On the other hand, late in some drought years there was hardly enough water to keep a trout wet and by the following spring we’d lost whole age classes of larger fish to winterkill.

These are undammed streams, so it’s all about rain and snow, heat and cold, absent the human greed, shortsightedness, and lawsuits that begin to kick in at the first irrigation head gates. Once the runoff comes down in a normal year, the online readout from the gauging stations forms a gentle wave: up slightly at night as the day’s snowmelt reaches the gauge and down slightly during the day to reflect the cold, high-elevation nights. It looks like the slow heartbeat of a large animal at rest, disturbed only by the occasional thunderstorm.

Over time I’ve learned to hope for normal seasons, but enjoy the fat years all the more knowing they won’t last and endure the poor ones in the equally secure knowledge that things will eventually turn around. I’m not sure this has taught me to take a longer philosophical view of things, but it’s at least shown me the qualities of character that would require.

I no longer fish the stretch of the main branch that flows through town and past the place where my old house used to stand. Over the last thirty years there have been two so-called improvement projects done there. They were both undertaken by people with the best intentions and have attracted the attention of more fly-fishers, but what was once a pretty stretch of trout stream now looks like a suburban water feature and the fishing is nowhere near as good as it was under the regime of benign neglect this little river used to enjoy.

The once-sleepy little town has gone in the same direction. After the influx of peripheral hippies that I was part of came the yuppies, Gen Xers, millennials, and more recently hipsters with their big beards, flannel shirts, and skinny jeans; many of them are the kind that move to a town with dirt streets because they think it’s charming, and then complain about the dust. Where there were once no stoplights, there are now four; where what passed for traffic once consisted of pickup trucks and big American sedans, there are now sometimes more bikes than cars, and the cup of coffee that used to cost a quarter now runs three dollars, although, to be fair, that’s mostly just inflation and the coffee is a lot better than the dishwater-strength Folger’s we used to get.

And speaking of inflation, the town can’t grow much because it’s surrounded on three sides by open public land, so real estate prices have climbed to meet the growing demands of gentrification, surprising the hell out of the few remaining natives. When the time finally came for me to cash out and blow town again, my old place was worth so much more than I’d paid for it—not the house (they bulldozed that within a week of the closing) but the land it sat on—that I could relocate north into the next county to a better old house on some acreage with more mule deer and rabbits than neighbors. A man in the business once told me that your best allies in real estate are longevity and the dumb luck to want out when others want in, and in fact this was the perfect move. I didn’t even lose any of my home water. I just added twenty minutes to the commute.

I did briefly consider moving away entirely—maybe to one of the places where I’d fished for a week, caught bigger trout, and come back thinking, You know, I could live there—but it turns out I guessed right back in my thirties: the roots eventually grow too deep to be pulled up without permanent damage. So instead I became one of those guys who give directions like “Go through town and turn right where the old lumber yard used to be.”

I now mostly stick to the upper forks of the drainage, through the canyons and on up into the headwaters, even though at least in their more accessible stretches some of these creeks have gotten noticeably more crowded. That’s because the population of the state has more than doubled since I moved here and fly-fishing, which was still a sporting backwater in the 1970s, is now as fashionable as skiing. So people keep moving here because it’s a beautiful place to live, but no one ever leaves for the same reason. The upshot is that it’s ever so slightly less beautiful than it once was, although you wouldn’t notice that if you hadn’t been here all along to see it happen.

And yes, it’s disheartening to find a stranger standing in what was once your secret pool and it’s either more or less disheartening in direct relation to how much trouble you went through to get there. Consequently, it’s easy to conclude that this upstart is fishing it all wrong, although it’s best not to hang around and watch, hoping to have that opinion verified. We local fishermen are widely believed (if not by others, then at least by ourselves) to have our home waters wired, but as Robert Traver pointed out, sometimes it’s the out-of-town nimrods who come in with fresh eyes, new ideas, and the latest fly patterns and proceed to fish circles around us. That does sting a little, but the deeper wound is that what were once our little secrets have become common knowledge.

For a long time the obvious solution to more people was simply to go earlier and hike farther than anyone else, thereby outdistancing the competition. That still works, but it now takes longer. I noticed that at some point the strategy of hiking farther and the reality of getting older began to diverge in inconvenient ways. It sneaks up on you, but eventually a mile at altitude begins to feel like a mile and a half, then two miles, and so on. I won’t dwell on this, but if you’re still curious you should read the late Donald Hall’s excellent book Essays after Eighty. It will either ease your fears about old age or make you vow to shoot yourself at age seventy-nine.

I suspect that I now fish this water differently than I did more than four decades ago, although I’m not sure I can put a finger on exactly how. It’s true that we all develop a fishing style tailored to the water we’re most familiar with—ranging from balls-to-the-wall to methodical to meditative—but it’s also true that every day out constitutes its own little self-contained drama and no two are exactly alike.

Some days I fish with a kind of quasi-scientific curiosity, casting to every inch of water and noting where the takes come from as if I were studying the characteristics of holding water. Other days I move right along, cherry-picking the known honey holes, calling my shots, congratulating myself when I’m right, and instantly forgetting about it when I’m wrong. Usually I’ll fish a size 14 or 16 dry fly trailing a lightly weighted soft hackle dropper of the same size. Other days I’ll just fish the dry fly, wanting to hook only those trout that are willing to come the full distance to the surface, if only because the take is such a pretty sight.

When I’m fishing with certain friends we’ll leapfrog from pool to pool and compare notes later. With others we’re more likely to trade off, with one of us casting and the other offering commentary like an announcer at a chess tournament, only not as serious.

When I’m fishing alone I’ll occasionally just walk the creek waiting for some sign to start casting and figuring I’ll know it when I see it. Sometimes it’s as obvious as a sputtering hatch and a pod of rising trout. Other times it’s something peripheral, like a patch of ripe raspberries or a few doorknob-size boletus mushrooms so small and fresh they’re not yet wormy, that makes me stop. (I carry brown paper bags in my daypack for these finds, although often enough I’ll just graze on the berries on-site.) On rare days it’s something as vague as a quality of the light or a certain stillness in the air that seems to make the water vibrate with possibility, but I think that’s less mystical than it sounds. It’s just that some of the things you know about your home water operate beneath the level of full consciousness and only reveal themselves disguised as intuition.

Sometimes I even have dreams about these creeks. In one that woke me up bolt upright before dawn I hook a fish so big that when I tighten the line and the fish begins to struggle I realize the bed of the stream I’m standing on is actually the fish’s back. I look down to see that the fist-size cobbles have turned to black spots on a bronze background, which would make this a brown trout the size of a school bus. That’s it; there’s no plot, no story line, just that one image that leaves me awake and blinking. Sometimes I have dreams so inexplicable that I assume they were meant for someone else and leaked into my head by accident, but that one—whatever it means—is mine alone.

I do love to catch trout—it becomes a hard habit to break—but more often now I find myself going out close to home not to clean up on fish, but just to prove to myself that they’re still there. So far they always have been, although they’re more or less cooperative depending on a hundred variables that can change by the hour. But in fact, these creeks near home have held up better over more than half my lifetime than anything else I can think of.

I no longer wonder, as I once did, how things might have gone if I’d settled somewhere else: maybe on a bigger, snazzier watershed that people travel long distances to reach hoping for blanket hatches and trout that regularly crack 20 inches. I can and do go to places like that when I get the chance and when I get back home I’m happy where I am.

I only have one friend that I’ve known for as long as I’ve fished my home water. We don’t see that much of each other anymore, but when we do get together—usually to go fishing—we pick right up in the middle of a nearly half-century-long conversation that will end only with one of our funerals. I’ve fished a lot of places and met a lot of people, but there are only a handful of streams that I know inside out and an equally small number of people whom I consider to be close friends. But a few of each is enough when you’re loyal as a dog to all of them.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (August 5, 2020)

- Length: 240 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501168581

Raves and Reviews

"Shrewd, perceptive and wryly funny. . . . Mr. Gierach, the man who coined the term 'trout bum,' is arguably the best fishing writer working."

– Bill Heavey, The Wall Street Journal

“Gierach’s inviting, down-to-earth, and humorous work shares a deep love of fly-fishing and the ways it can be a metaphor for life.”

– Publishers Weekly

“From the zen of aging to the tao of tying flies, from palm-size brook trout to leg-length muskies, Dumb Luck and the Kindness of Strangers is the best yet from fly-fishing’s favorite cosmic uncle.”

– James R. Babb, author of Fish Won’t Let Me Sleep

"Those looking for how-to tips will find plenty here on rods, flies, guides, streams, and pretty much everything else that informs the fishing life. It is the everything else that has earned Gierach the following of fellow writers and legions of readers who may not even fish but are drawn to his musings on community, culture, the natural world, and the seasons of life."

– Kirkus Reviews

“John Gierach is an original, which is why each new book is welcomed by so many anglers as joyously required reading. Pardon the interdisciplinary reach, but Gierach’s stories are rather like McCartney's music—on the one hand vitally fresh, yet on the other hand instantly familiar. Don't worry about how he does that—just keep reading.”

– Paul Schullery, author of The Fishing Life and A Fish Come True

“John Gierach gives us fishing as the alert life; people, places and rivers seen by a first-rate noticer whose amiable disposition never alarms the prey.”

– Tom McGuane

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Dumb Luck and the Kindness of Strangers Hardcover 9781501168581

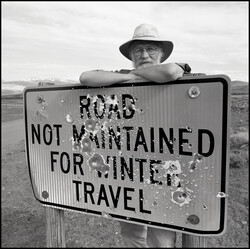

- Author Photo (jpg): John Gierach Photograph by Michael Dvorak/@mikedflyphotography(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit